Corn Fed Beef and Methane Gas

Carbon Footprint Comparing Betwixt Grass- and Grain-finished Beefiness

Published Mar. 2017 | Id: AFS-3292

By Ashley Broocks, Emily Andreini, Megan Rolf, Sara Place

- Bound To:

- Summary

- Literature Cited

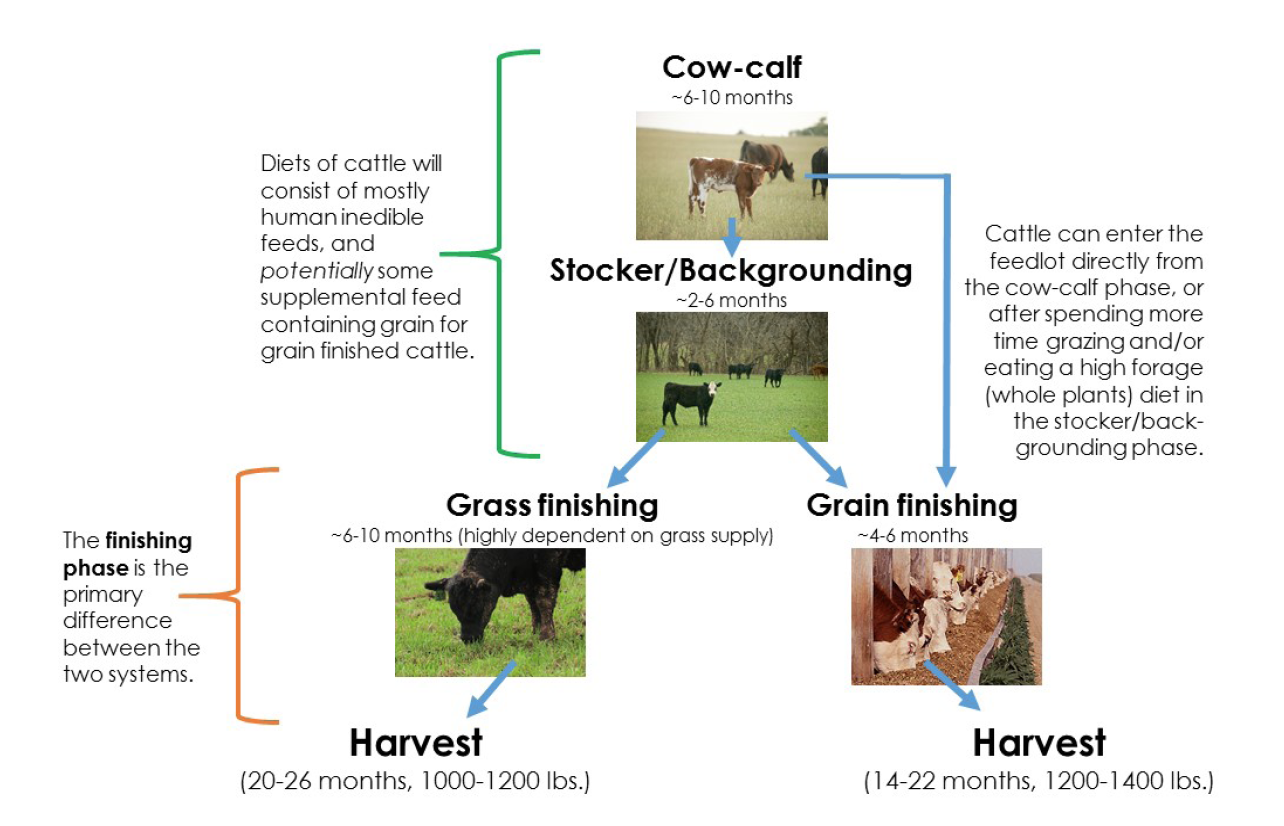

Even though cattle live the bulk of their lives on pasture, the type of finishing system notwithstanding impacts the carbon footprint of beef. The carbon footprint for beef is all the greenhouse gas emissions produced during the production of beef divided by the full amount of beef produced past the organisation. Beef production consists of three main phases: cow-calf, stocker/backgrounding and finishing (Figure i). The outset phase of the animals' life is spent nursing and grazing on pasture along with its mother. After calves are weaned, they typically spend boosted time grazing the crop residue that remains subsequently harvesting grain or grazing forage pastures and grasslands. During this time, known as the stocker or backgrounding stage, they gain additional weight every bit they prepare to enter the finishing stage. The finishing phase is the final phase before the cattle are sent for harvest. Cattle entering the finishing phase are typically 12 to 16 months old, and remain in this phase until they have achieved a level of fatness, or stop, that will provide a positive eating experience for consumers. The main departure in carbon footprints between grass- and grain-finished beefiness occurs as a result of the time spent in the finishing phase, the type of feed consumed and the body weight of the cattle at the end of the finishing phase.

Effigy one. Beef cattle life bicycle for grass-finished and grain-finished beef in the U.S.

Cattle entering the feedlot for finishing swallow a nutrition containing corn along with byproducts (such as distillers grains leftover after ethanol production and corn gluten feed after corn fructose production), vitamins and minerals, and small quantities of forage or roughage (such every bit hay). Grain-finished cattle remain in the feedlot for approximately 4 to six months and are sent for harvesting at xiv to 22 months of age. Grain-finished cattle reach market weight faster than grass-finishedane,2 cattle because the diet received is higher in free energy, which results in rapid and efficient weight gain. In contrast, grass-finished cattle gain at a slower rate due to the fodder-based diet they consume and typically go to harvest at 20 to 26 months of age and at a lower weight than grain-finished animals. Grass-finished cattle may finish either faster or slower than this age range, depending on the provender and grass resources available to the beef producer (e.grand., the growing season is shorter in northern states, which may shorten the finishing flow and lead to lighter weights at harvest). The difference in harvest weights translates into different numbers of U.South. citizens that could exist fed per animal (Tabular array 1). Utilizing forage as the primary source of feed also contributes to an increased carbon footprint for grass-finished beeftwo, because high forage diets (e.g., grass) produce more methyl hydride emissions (a greenhouse gas 28 times more strong at trapping heat in the globe'southward temper as compared to carbon dioxide3) from the animal's digestive tract than higher-free energy, grain-based diets. The combination of consuming a higher-energy, lower-forage diet, shorter time spent on feed during finishing and heavier carcass weights translate into an 18.5 to 67.v per centum lower carbon footprint for grain-finished beefiness as compared to grass-finished beefane,2.

Table 1. U.S. citizens fed for one year per creature for grain-finished and grass-finished beef citizens.

| Finishing organisation | Harvest live weight, lbs. | Dressing % | Carcass weight per animal, lbs. | U.Southward. citizens fed per animate being* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grass-finished | 1,100 | 0.58 | 638 | viii |

| Grain-finished | ane,300 | 0.64 | 832 | 10.4 |

∗Assuming eighty.i pounds of carcass weight availability per capita in 2013.

Even though grass-finished beef has a college carbon footprint, it does take some sustainability advantages. Grass-finished animals utilize homo inedible foodstuffs as the primary source of energy and nutrients for their entire lifetimes. Beefiness cattle can use forage grown on land non suitable for crop production, and thus produce human being edible food from a resources non otherwise able to produce nutrient. Additionally, grasslands and pastures can sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which can help to mitigate global climate change. Research has shown there is an advantage for grass-finished beef production over grain-finished beef production when expressing feed conversion as human edible energy returned per unit of measurement of homo edible energy consumed past the cattletwo,6. Bookkeeping for carbon sequestration of pasture grass-finished beef could lower the carbon footprint of grass-finished beefiness by 42 percent2. In contrast, approximately 18 percent of feed intake per unit of carcass weight will occur in the feedlot for grain-finished cattle5. Traditionally, the feed consumed past cattle in feedlots was primarily corn. In many modern feedlots, cattle now eat diets high in byproducts feeds, such as corn gluten feed and distillers grains. These byproduct feeds are homo inedible residues from human food and fuel production. Ultimately, there are tradeoffs between the two beef production systems; all the same, beef producers using either system tin sustainably meet consumer demand for beef.

Summary

At that place are tradeoffs in different aspects of sustainability when comparing grain-finished and grass-finished beef production systems. Grain-finished beef has a lower carbon footprint than grass-finished beef due to more efficient utilization of feed in the finishing phase, fewer days on feed and greater amount of beef produced per animate being. Nonetheless, grass-finished beef contributes to sustainable beef production by utilizing forage resources during finishing to produce nutrient from man-inedible plants.

Literature Cited

- Capper, J.L. 2012. Is the grass always greener? Comparing the ecology bear upon of conventional, natural and grass-fed beefiness product systems. Animals. two:127-143.

- Pelletier, Due north., R. Pirog, and R. Rasmussen. 2010. Comparative life cycle environmental impacts of three beefiness production strategies in the Upper Midwestern United States. Agric. Sys. 103:380-389.

- IPCC. 2013. Climatic change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of working grouping I to the fifth assessment study of the IPCC. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK.

- USDA. 2014. Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System.

- Rotz, C.A. South. Asem-Hiablie, J. Dillion, and H. Bonifacio. 2015. Cradle-to-farm gate environmental footprints of beef cattle production in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. J. Anim. Sci. 93:2509-2519.

- Wilkinson, J.Yard. 2011. Re-defining efficiency of feed use by livestock. Animal. 5:1014-1022.

Ashley Broocks

Graduate Student

Emily Andreini

Graduate Student

Megan Rolf

Assistant Professor

Sara Place

Assistant Professor, Sustainable Beef Cattle Systems

- Share Fact Sheet

Was this information helpful?

YESNO

Source: https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/carbon-footprint-comparison-between-grass-and-grain-finished-beef.html

0 Response to "Corn Fed Beef and Methane Gas"

Post a Comment